[ad_1]

The Psychedelic Meeting attracts a sure sort of clientele. The partitions of the group’s Manhattan assembly house are lined with LSD blotter artwork and Alice in Wonderland paraphernalia. Rows of bookshelves are full of esoteric titles on tryptamines, DMT entities, and magic-mushroom alchemy. The individuals who collect there converse simply on matters starting from visits with Mom Ayahuasca within the jungles of Peru to suggestions for throwing a profitable group MDMA expertise.

Suffice to say, those that discover their manner there are inclined to test sure containers: liberal, Northeastern, skilled with mind-altering substances. They don’t are typically politically and religiously conservative lawmen from one of many reddest states within the U.S.

However on a sunny morning in Could, that is precisely who walked in: Bryan Hubbard, an legal professional contemporary from Lexington, Kentucky. Hubbard was on a drug-themed go to to New York Metropolis—a part of a really surprising flip of occasions that started in 2022 when he launched into a yearslong journey into the guts of psychedelic-assisted therapeutic. His cease on the Psychedelic Meeting “was simply sort of the icing on the surreality cake,” he says.

“If somebody had instructed me as a 25-year-old man—a staunchly straight-laced, sq., institutionalist Republican—that I’d have undergone a metamorphosis which might lead to me being in New York Metropolis for the development of God’s drugs to heal God’s folks, I’d have instructed you that I had gone insane and one thing catastrophic will need to have occurred in my life,” he says.

By “God’s drugs,” Hubbard means the psychedelic drug ibogaine. Particularly, he was serious about its potential means to rid folks of dependancy to opioids and different habit-forming substances.

Hubbard was in a novel place to be wanting into ibogaine in 2022: He had lately been named head of Kentucky’s Opioid Abatement Advisory Fee, a activity drive charged with divvying up half of the state’s $842 million settlement from nationwide litigation that accused opioid producers and distributors of exacerbating the opioid epidemic. Hubbard and his colleagues had been presupposed to disperse the funds throughout whichever state packages would ship the most important bang for the buck in serving to Kentuckians get better and rebuild.

A lot of the grants would go to established strategies of prevention and therapy. However Hubbard believed extra was wanted than the established order. Methadone and buprenorphine (underneath the model identify Suboxone) are the gold-standard remedies for opioid dependence, however anyplace from 40 p.c to 80 p.c of people that take these artificial opioids relapse. So whereas present remedies do save lives, they aren’t a panacea. In the event that they had been, Hubbard factors out, Kentucky’s overdose deaths wouldn’t have risen by greater than 50 p.c since 2019.

On July 29, 2022, Hubbard felt he bought the lead he was in search of. He was on the cellphone with Julia Blum, a journalist he admired, selecting her mind about under-the-radar remedies for substance use problems when she requested if he’d ever heard of ibogaine.

“I’ve by no means heard of it in my life,” he replied. “Inform me extra.”

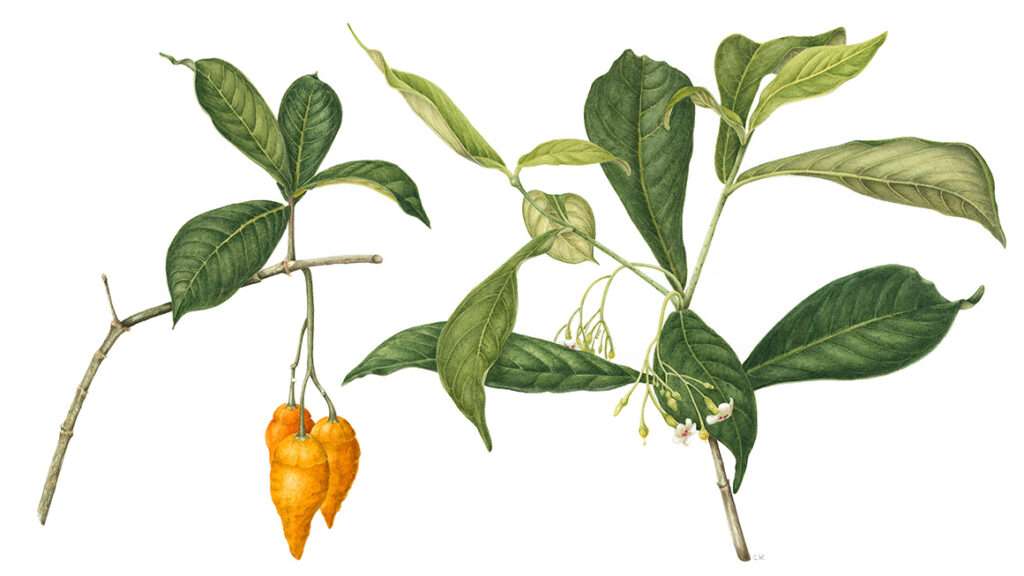

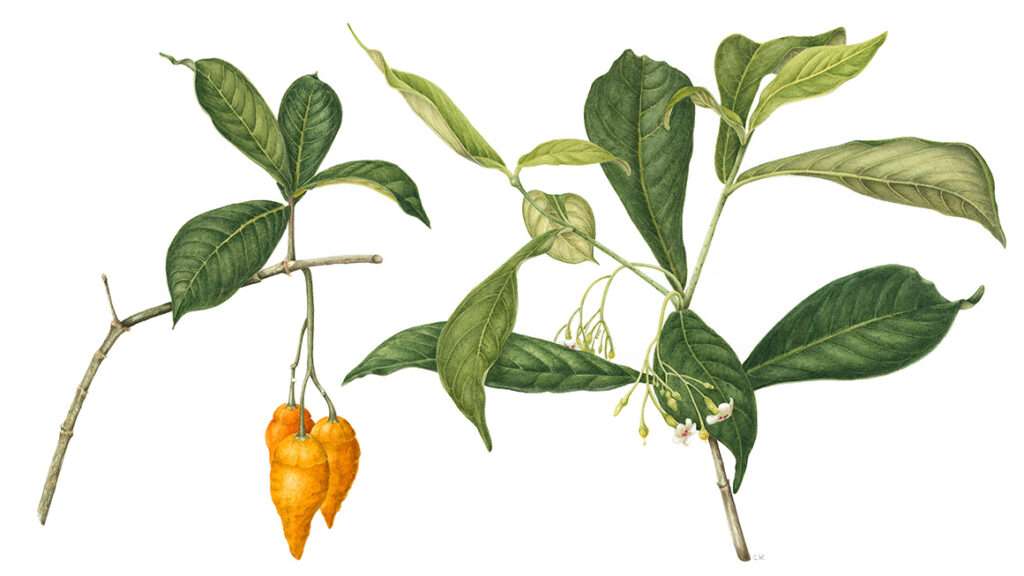

Blum gave him a fast crash course on the drug. Ibogaine is an alkaloid primarily produced by a Central African shrub referred to as iboga. It is one of the vital potent mind-altering substances in existence, triggering experiences that final 30 hours or extra. Usually it leaves the person endlessly modified.

In Gabon, the place iboga has been used for hundreds of years, folks flip to the shrub to acquire messages from ancestors and spirits and to get readability on their life’s route. Within the West, ibogaine extra lately has turn into identified for a distinct software: serving to to rid folks of substance use problems.

Anecdotal information and a few scientific research recommend that a number of psychedelic medicine, together with ibogaine, could possibly assist root out the sources of post-traumatic stress dysfunction (PTSD) and different psychological maladies. Ibogaine stands out, nevertheless, for what could also be a novel means to abruptly finish addiction-related cravings whereas additionally permitting the particular person to bypass the agonies of withdrawal.

“It is a lengthy, intense journey throughout which the drugs illuminates the roots of the dependancy by way of dreamlike visions that usually contain recollections,” Blum defined to Hubbard. Many individuals additionally emerge with a newfound sense of which means and function.

“The place can I study extra?” requested Hubbard.

Comparatively few scientific research have been carried out on ibogaine. However the analysis that does exist is encouraging. At a clinic in St. Kitts, for instance, nearly all of 191 sufferers who obtained a single dose of ibogaine efficiently detoxed from opioids or cocaine. The truth that this research was carried out in St. Kitts highlights a significant downside, nevertheless: Ibogaine is a Schedule I substance in the USA, so it’s unlawful on this nation. People who want to attempt it should journey to Mexico, Brazil, Costa Rica, Colombia, South Africa, or one other place the place it’s out there. This retains ibogaine therapy “solely within the realm of people that have cash,” says Nolan Williams, a Stanford psychiatrist and neurologist who has carried out analysis on the drug.

Hubbard got here to treat ibogaine as a possible resolution for addictions. Greater than that, he noticed a robust substance able to therapeutic the “profound religious affliction” that he believes is on the core of what drives most individuals to succeed in for the capsule bottle or needle. “As technologically superior and as rich as we’re, we live in a brutally dehumanizing period,” he says. We have now erected false partitions round ourselves which have given rise to an epidemic of loneliness, divisiveness, and despair, he continues, and we’ve turn into complacent within the face of forces that manipulate and exploit us. We have now forgotten “how fabulously particular and delightful” every of us is, he says, “just by advantage of being a human being.”

Hubbard hoped ibogaine could possibly be the wrecking ball that smashed by way of all of that. And in his position directing Kentucky’s fee, he noticed an opportunity to rework the state—an epicenter of the opioid disaster—right into a nationwide chief in ibogaine analysis. He hatched a plan for Kentucky to host scientific trials to determine the drug’s security and efficacy so the U.S. Meals and Drug Administration (FDA) would approve it as an dependancy therapy.

“What will get me fired up and able to go each morning,” Hubbard says, “is probably considering that there may be one thing inside me that God finds appropriate to make the most of to pursue the emancipation of my fellow human beings from any subjugation that they may be struggling.”

And the best way Hubbard sees it, opioid abuse is in regards to the largest tyrant of the soul and subjugator of human beings that there’s.

Destitution In all places

Though the lilt of Hubbard’s Appalachian accent is so pronounced that it appears virtually placed on, he possesses the diction of a nineteenth century literato. He’s bodily formidable, able to bench-pressing over 400 kilos, and his beard and shoulder-length hair are harking back to a Viking. However his blue eyes turn into glassy and his voice trembles with emotion when he discusses the tragedies of opioid dependancy.

Hubbard grew up in Russell County, Virginia, a lush area of mountain ridges and valleys that sits atop a number of the nation’s richest mineral wealth. Regardless of its huge coal reserves, almost 1 / 4 of the inhabitants lives under the poverty line. In Hubbard’s small group, a handful of highly effective households owned and managed all the pieces, he says, whereas the remainder of the citizenry had been “the nobodies.”

Hubbard’s household fell into that latter class. His dwelling life was “chaos,” he says. His earliest recollections are his mother and father’ screaming matches. Happily, his grandparents took an lively position in his upbringing, stopping him from winding up “in a ditch someplace.” His grade faculty–educated grandfathers each had been lacking fingers and suffered from silicosis from years of working the mines, however they all the time exuded happiness, optimism, and “immense knowledge,” Hubbard remembers. The one particular person he idolized as a lot as his grandfathers was President Ronald Reagan, whom he imprinted on “similar to a gosling to its mom goose.” Earlier than Hubbard had even completed elementary faculty, he determined that, like Reagan, he would dedicate his life to serving his fellow People. And what higher manner to do this, he thought, than to pursue the noble observe of legislation?

Hubbard’s starry-eyed notions about his chosen profession path had been rapidly dispelled by his authorized schooling on the College of Kentucky. He realized that legislation typically had “nothing to do” with goal fact or justice, that energy regularly trumps fact, and that the authorized system is often utilized by these with energy to crush individuals who have no. “Our judicial system is a shame, interval,” he says.

However Hubbard compartmentalized his disappointment and bought his diploma. After graduating in 2000, he took a job at a Lexington insurance coverage protection agency that dealt with all of Walmart’s employee compensation claims for the state. The gig was presupposed to be short-term, however a 12 months in, his boss fell off a ladder and died. He inherited her pile of 300 instances and wound up staying for the following 17 years.

As time handed, Hubbard seen a conspicuous sample within the instances he was seeing: A lady between the ages of 45 and 70 from the Appalachian area of Kentucky, who had spent her total life in a low-wage job, would are available in complaining of excruciating ache from a work-related harm. The harm was minor sufficient that it ought to have taken six months or so to heal following therapy, and diagnostic checks couldn’t pinpoint the anatomical supply of her ache. But right here she was, in agony. Inevitably, Hubbard says, she can be “loaded up” on a specific cocktail of medicine: OxyContin, Xanax, and Prozac.

Sooner or later, Hubbard was driving by way of city, pondering the way it could possibly be that ladies who had been taking sufficient opioids to knock out a horse may nonetheless be in ache, when a thought struck him: Their bodily ache was a symptom of a profound emotional and religious ache that no quantity of prescription drugs may alleviate. “That they had reached a degree in life the place they acknowledged that they had been going to be residing on the useless finish of welfare subsistence to their grave, with none prospect of getting a life that we might understand as being one that’s lived with freedom and dignity and management over future,” Hubbard says. “That work accident…was the straw that broke their backs.”

Hubbard didn’t have any peer-reviewed scientific journal articles to again up his hunch. However he felt positive he was proper.

Clear, Accountable, Accessible

In 2017, Hubbard moved on to a job as Kentucky’s deputy commissioner of the Division for Earnings Assist. There, he says, he solidified his fame as “a take-no-prisoners…get-it-done-without-compromise dude.”

Hubbard rooted out substantial inside rot, for instance, in Kentucky’s Youngster Assist Enforcement program, which is run by 120 elected county attorneys. Monetary controls and oversight had been nonexistent. Cash was disappearing, and round 40 of the directors had been housing this system on property they personally owned, permitting them to gather hire from the state. Hubbard’s crew uncovered grime that led to a federal prosecution of 1 corrupt administrator and ongoing FBI investigations of three others.

When Democrat Andy Beshear grew to become governor in 2019, Hubbard was promptly faraway from his job on “hour one among day one,” he says. “I’ve no query that that was a favor performed to the [state-wide Kentucky] County Attorneys Affiliation,” which “had had fairly sufficient of me.” (Beshear’s workplace declined an interview request for this story.)

Daniel Cameron, the state’s new Republican legal professional normal, then appointed Hubbard to supervise the Workplace of Medicaid Fraud and Abuse Management. Hubbard’s workplace doubled legal indictments and convictions throughout the subsequent 12 months. Lots of these convictions had been for fraudulent prescriptions of Suboxone, one of many artificial opioids used to deal with opioid dependancy. Relatively than curbing the disaster, the drug was being diverted and offered on the road.

By April 2022, Hubbard had developed sufficient experience in opioid dependancy and the numerous federal, state, and nonprofit entities tied to it that Cameron tapped him to guide the Opioid Abatement Advisory Fee. As he accepted the place, Hubbard contemplated the best way to ship probably the most worth doable to Kentucky. The overwhelming majority of the funds can be invested in strengthening present infrastructure for restoration and prevention. However Hubbard was additionally serious about discovering new approaches.

Just a few months later, he bought in contact with Blum, and his journey into the world of ibogaine had begun.

The ‘Ibogaine A-Workforce’

Just about everybody who is aware of something about ibogaine has heard of Juliana Mulligan. Mulligan spent most of her 20s battling opioid dependence. All typical remedies failed her, and she or he had endured overdoses, hospitalizations, homelessness, bodily assault, and incarceration. In 2008, she heard about ibogaine from a good friend and sought it out as a last-ditch effort to avoid wasting her life.

Mulligan very almost died within the course of. The supplier she present in Guatemala gave her double the protected dose, inflicting Mulligan to enter cardiac arrest. Regardless of the depth of the expertise, her first sensation upon waking up within the hospital was a sense of liberation.

“It felt like a thousand kilos of guilt, disgrace, and remorse had been lifted off of me,” Mulligan remembers. She had no cravings for opioids and solely gentle signs of withdrawal, and she or he felt a brand new readability about her life’s function. “I all of the sudden noticed that my years of struggling had been truly my coaching to do the work I used to be meant to do,” she says: to advance ibogaine as an accessible therapy and to vary the largely ineffective mainstream substance use dysfunction therapy system.

That was 13 years in the past, and Mulligan has not touched an opioid or skilled a yearning for one since. She lives in New York Metropolis, the place she is a licensed psychotherapist who works with shoppers earlier than and after ibogaine therapy. “I get emails on a regular basis from folks asking me questions,” she says. So when a message landed in her inbox from “some man from Kentucky,” she did not assume a lot of it however agreed to take his name.

As Hubbard defined his place, she mentioned to herself: “Holy shit, this can be a large deal.” She and her colleagues had been struggling for years to give you a practical plan for making ibogaine an FDA-approved pharmaceutical—a course of that, on common, requires half a billion {dollars}. Hubbard was the primary particular person ready of any political energy who had expressed curiosity in ibogaine, one thing Mulligan “by no means anticipated from a Republican Kentucky man with an accent like that.”

So Mulligan launched into motion, connecting Hubbard with “all my ibogaine A-team.” He responded with enthusiasm, dedicating nights and weekends to studying all he may in regards to the drug and connecting with dozens of researchers, philanthropists, and activists. He and his spouse spent $5,000 of their very own cash to journey to New York Metropolis to fulfill Mulligan and her colleagues—a “private funding,” Hubbard says, find an answer for Kentuckians.

Nobody is aware of how precisely ibogaine works. In pharmacological parlance, it is a “soiled drug”—one which hits receptors throughout the mind’s varied methods. Researchers have little thought of why it will be efficient for treating substance use problems. “We perceive just one p.c of what it does,” Mulligan says, “which can be why it is just a little bit harmful.”

Researchers have historically shied away from finding out ibogaine due to its cardiac threat. “The most important concern [about ibogaine], in my view, is the shortage of regulation in international international locations and the danger concerned in searching for this therapy in doubtlessly unregulated environments,” says Alan Davis, an affiliate professor of social work and director of the Heart for Psychedelic Drug Analysis and Schooling at Ohio State College. “We desperately have to reply questions on security and what’s occurring on the market proper now in these clinics.”

From 1990 to 2008, no less than 19 folks died after taking ibogaine, and a trial participant in New Zealand additionally died in a research printed in 2017. There may be compelling proof, nevertheless, that the drug’s cardiac threat could be mitigated by way of intravenous magnesium. An ibogaine facility in Mexico referred to as Ambio Life Sciences has given magnesium to round 1,000 shoppers since 2014, and none has skilled a critical arrhythmia.

Whereas present proof means that ibogaine is “no less than pretty much as good as and doubtlessly simpler than different remedies for opioid use dysfunction,” Davis says, it is “very troublesome to know for positive” as a result of scientific trials have but to be accomplished on the drug. He and his colleagues try to no less than partly fill that information hole by conducting an FDA-informed real-world survey of people that have used ibogaine to handle dependancy or different problems. For now, a “diploma of skepticism is warranted,” he provides—however that can hopefully change as extra information are collected about ibogaine’s effectiveness.

Anecdotally, the outcomes for many individuals who’ve taken ibogaine have been “outstanding,” says Amber Capone, co-founder and CEO of Veterans Exploring Therapy Options (VETS), a nonprofit that helps American veterans entry psychedelic remedy overseas, together with at Ambio. “I’ve seen folks with lively suicidal ideation or makes an attempt, people who find themselves barely surviving life, fully regain their lives and futures and restore their households’ hope,” she says.

Capone and her husband—Marcus, a medically retired Navy SEAL—created VETS after Marcus took ibogaine and skilled profound aid from signs of PTSD and traumatic mind harm (TBI). VETS has footed the invoice for almost 1,000 veterans since 2019, however the want far outstrips its capability: The group has to show away “the overwhelming majority” of these searching for assist, Capone says.

The one manner to make sure that ibogaine is accessible to everybody within the U.S., provides Williams, the Stanford researcher, is to get FDA approval and Medicare protection of the therapy. If that did occur, any fears about doable diversion of the mind-altering, presently prohibited drug would most likely be unfounded, says Tom Feegel, CEO of Beond Ibogaine, a therapy heart in Cancún, Mexico. “It is exceptionally unlikely that individuals would select to make use of this explicit psychedelic for a leisure function,” Feegel says.

Of Beond’s roughly 500 annual shoppers—most of whom are People—60 p.c come to handle opioid use, 13 p.c alcohol use, 9 p.c despair, and seven p.c cocaine use. Just a few additionally come for therapy of PTSD and TBI. Simply 4 p.c are there for “well being and optimization,” a broad class that features folks serious about self-exploration, private progress, enhanced psychological acuity, and assist navigating life transitions.

Seasoned psychonauts (a time period for individuals who have intensive expertise with mind-altering medicine) additionally typically discover their approach to Beond, curious to attempt “the Mount Everest of psychedelics,” Feegel says. This class of consumer often is available in considering they need “a so-called psychospiritual” journey, he notes, however most wind up getting “what they want, not what they need.”

“What they want” tends to appear like a 10-to-12-hour, deeply introspective dive into their total life and lineage, conveyed to them in additional element than they ever may have imagined. They often additionally emerge with new readability on how finest to spend their remaining time on Earth.

“There are numerous different psychedelics which can be much more enjoyable and so much much less demanding,” Feegel says. “Ibogaine will not be a celebration favor.”

‘Akin to a Miracle’

By January 2023, Hubbard felt assured sufficient to introduce the ibogaine thought to Cameron. It was, he instructed the legal professional normal, a “Manhattan Venture alternative.”

Hubbard confirmed Cameron a PowerPoint presentation explaining the drug and proposing a public-private partnership to launch an FDA-approved scientific trial inside Kentucky to research ibogaine’s means to deal with opioid use dysfunction. He prompt paying for this with $42 million from the opioid settlement—5 p.c of the full—unfold over six years, with that cash matched by a drug developer. Ibogaine, Hubbard instructed Cameron, gave Kentucky the chance to pivot from a “state that has been on the again finish of America for nearly its total trendy historical past” to the chief of “a revolution” in dependancy therapy.

Cameron’s workplace declined an interview request for this story. However Hubbard says the legal professional normal was supportive, and Cameron made remarks at a Could 2023 press convention indicating as a lot. Most of Hubbard’s colleagues on the fee bought on board too. Fee member Karen Butcher—whose son, Matthew, died from an opioid overdose in 2020—remembers seeing Hubbard’s PowerPoint slides and feeling “like I used to be watching one thing that was akin to a miracle. All I may assume was, if my son had been alive right this moment, we might be headed to Mexico.”

One of many strongest dissenters from ibogaine enthusiasm was Sharon Walsh, a professor of behavioral science, pharmacology, pharmaceutical sciences, and psychiatry on the College of Kentucky, the place the ibogaine scientific trial would seemingly happen. “If the main target is on opioid withdrawal, we’ve drugs which can be already authorised for opioid withdrawal,” she acknowledged at a June 2023 fee assembly. “These are very efficient medicine. I am unsure why we’d like different medicine to focus on opiate withdrawal.”

Days later, Walsh resigned from the fee. In emailed responses to questions, she mentioned her resignation was because of elevated work duties. She reiterated that opioid withdrawal is “simply treatable” and that what’s actually wanted is “drugs that may forestall somebody from returning to opioid use.”

“I’d be completely ecstatic to see a real ‘treatment’ for opioid use dysfunction make it to market or every other therapy that fills the unmet want as this lethal dysfunction has devastated the USA,” Walsh added. “Actually, I’d encourage any firm that has promising information to share their early security and efficacy information with the Meals and Drug Administration and request a fast-track approval.”

Walsh was not the one skeptical voice after Hubbard raised the ibogaine thought. At a press convention in Could 2023, Beshear chided the fee for proposing such a big sum for ibogaine in comparison with legislation enforcement. “In case you solely present $1 million to legislation enforcement and $42 [million] to pharma, it does not appear to be you are backing the blue,” he instructed reporters. “It looks like you are backing Huge Pharma.”

Odd Kentuckians, in contrast, appeared supportive of the ibogaine proposal. “In the midst of this 60-plus p.c Trump-voting, Bible Belt believing-in-hellfire-and-brimstone purple state, there’s a large quantity of natural grassroots assist for [ibogaine’s] development,” Hubbard says. An impartial evaluation of a whole lot of social media responses to the ibogaine proposal prompt that almost all Kentuckians considered it favorably.

Three public hearings in regards to the drug—all of which ran over 4 hours—additionally drew crowds. Nolan, Mulligan, and the Capones testified, as did an FDA consultant who confirmed that it was doable to get approval for an ibogaine scientific trial. Dozens of others spoke as nicely, together with veterans, mother and father, and former opioid customers. Lots of the testimonies had been extremely emotional, and a few audio system availed themselves of a field of tissues subsequent to the microphone.

Because the climate turned cool, ibogaine appeared poised for achievement. Hubbard had obtained commitments from Stanford College and several other foundations to assist Kentucky because it pursued scientific trials, and he was assured of majority assist from the fee. However he determined to carry off on voting till Williams’ newest ibogaine findings had been printed.

Williams’ research appeared in Nature Drugs in January. A single dose of ibogaine, he and his colleagues concluded, supplied vital reductions in measures of PTSD, despair, nervousness, and TBI-associated incapacity in 30 VETS-supported sufferers who undertook the remedy at Ambio. 13 members additionally had alcohol use dysfunction, and all considerably diminished their variety of consuming days after therapy with ibogaine. All the members obtained intravenous magnesium, and none skilled critical negative effects.

Ibogaine, in different phrases, appeared prepared for a U.S. scientific trial.

However by the point Williams’ analysis got here out, the hope of constructing Kentucky the positioning of that trial had pale. In November 2023, Cameron misplaced the governor’s race to Beshear—and Republican Russell Coleman, a former FBI agent and Mitch McConnell lawyer, was elected legal professional normal. The tides of energy had shifted, and ibogaine’s most influential political supporter was out of the sport.

Thwarted Breakthrough

Hubbard had suspected that one thing was off when he heard Coleman say that longtime FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had been one among his boyhood heroes. However previous to the election, the 2 males had developed what Hubbard thought was a “working friendship.”

Hubbard had given Coleman the identical ibogaine briefing he had offered to Cameron. However not like Cameron, Coleman had been cautious to stay impartial. Because the election approached, Hubbard began to wonder if Coleman was really the “impartial, reform-minded Republican” he had appeared in non-public dialog, or if he was “a part of the identical ol’ machine institution that is run Kentucky generationally now for many years.”

In December—after Coleman was elected however earlier than he took workplace—he referred to as a gathering with Hubbard. As Hubbard recounts the assembly, Coleman began by acknowledging that ibogaine “very nicely could have therapeutic worth.” However he rapidly pivoted to expressing his disagreement with the challenge and his “nice displeasure” with Hubbard’s public advocacy for ibogaine.

“You haven’t in any manner acted with any diploma of objectivity,” Hubbard remembers Coleman telling him. “You have not handled this with something aside from full-throated, full 100% supportive advocacy.”

“I have been an advocate for this as a result of I imagine in it,” Hubbard says he replied.

“The choice has been made,” Coleman mentioned, in accordance with Hubbard. “I’ll want your resignation by December 31.” (Coleman’s workplace declined an interview request for this story.)

The day after Christmas, Hubbard issued a 10-page resignation letter addressed to “The Individuals of Kentucky.” The ibogaine plan had failed, he wrote, as a result of it offered a “mortal risk” to the established order of energy and cash. “The chance for Kentucky to pioneer a breakthrough has been thwarted.”

Butcher, the ibogaine-supporting fee member, held out hope that the proposal may nonetheless transfer ahead in Hubbard’s absence. However that was rapidly dashed. Coleman appointed a former Drug Enforcement Administration agent to take Hubbard’s place as head of the fee. In an deal with that Coleman delivered in March, he requested members of the fee to “step again” from “the unproven and extremely costly scientific trial for a psychedelic that’s presently unlawful as a Schedule I drug.”

Listening to this, Butcher says, she felt “discouraged, disgusted, heartbroken, and disillusioned.”

Hubbard now thinks his ibogaine plan was all the time doomed to fail. He factors to an open supply evaluation of publicly out there data compiled by Reveille Advisors, a non-public intelligence agency primarily based in Denver. “We had been actually curious why there was a lot prompt animosity in the direction of the ibogaine proposal from the College of Kentucky and the present administration,” says Wes Anderson, Reveille’s director of operations.

Anderson and his associate, Rob, who prefers to withhold his final identify due to his investigative work, additionally had private pursuits in ibogaine. Anderson has a brother who resides homeless in Dallas, partly due to an opioid behavior, and Rob is a retired Particular Operations veteran with combat-related TBI. Their investigation, which they undertook professional bono, revealed monetary hyperlinks between those that opposed the ibogaine proposal and the opioid dysfunction therapy business.

Walsh, the College of Kentucky professor, for instance, earned almost $50,000 in consulting charges from firms that make buprenorphine and Naloxone in 2016 and 2018, the years for which Reveille may discover information. She has served as a scientific adviser for no less than eight such firms within the final three years, and she or he was an investigator on a profitable current scientific trial of long-acting buprenorphine. “If opioid use dysfunction medicines are challenged,” Anderson argues, “her life’s work will not be related.”

Walsh responded by e mail that this evaluation “couldn’t be extra unsuitable.” She confirmed that she has labored as a scientific adviser on substance use problems to pharmaceutical firms, U.S. authorities companies, and worldwide organizations. However she added, “I’m unclear why you have an interest in together with me in your article as I used to be not part of the hearings or voting associated to the difficulty of ibogaine. I had already left the Fee earlier than these occasions occurred.”

Jay Blanton, a spokesperson for the College of Kentucky, acknowledged by e mail that it’s regular and inspired for college school to work with each the private and non-private sectors. “Pharmaceutical growth can be a typical subject for business session as a lot drug growth—together with for many who advocate for ibogaine—happens inside the non-public sector,” he mentioned.

Hubbard rejects these arguments. Over the last 25 years, he claims, his alma mater has betrayed its land grant establishment mission of democratizing increased schooling and has turn into the equal of “a Fortune 100 company” with a multibillion-dollar financial footprint.

“Each transfer the College of Kentucky makes is animated by a cash lust,” Hubbard says. “Any suggestion that their educational positions are on no account influenced by their embedded monetary relationships is a slap within the face to the current historical past of academia’s prostitution to Huge Pharma, and to widespread sense.”

Reveille’s findings additionally prolonged to the politicians concerned in ibogaine choices. Beshear, it discovered, obtained about $225,000 in marketing campaign donations from pharma firms and their lobbyists and from opioid use dysfunction benefactors resembling restoration facilities, whereas Coleman obtained almost $200,000 from such donors. Beshear’s legislation agency represented Purdue Pharma in opposition to the state of Kentucky within the OxyContin case, and Coleman’s legislation agency is the lobbyist for DisposeRx, a medical disposal equipment that’s distributed with opioid prescriptions. Coleman’s agency—like Beshear’s—has additionally represented Purdue Pharma, Abbott Laboratories, and Merck in lawsuits in Kentucky. And though the 2 politicians are from reverse political events, Coleman’s agency donated over $35,000 to Beshear’s 2023 reelection marketing campaign—virtually matching the $37,000 donation from Beshear’s agency to Beshear’s marketing campaign.

Thickening the plot, in August, Coleman additionally recused himself from an FBI investigation into potential well being care fraud by Dependancy Restoration Care (ARC), a high-profile dependancy therapy supplier in Kentucky. In accordance with Reveille’s findings, associates of ARC and its chief govt officer gave $21,000 in money donations to Coleman’s election marketing campaign.*

Anderson emphasizes that each one of those findings are “simply observations” and “we’re not saying there was lively wrongdoing.” Hubbard, nevertheless, is satisfied that his ibogaine proposal had been reduce down by a “nexus of intertwined political and monetary pursuits.”

A Divine Conviction

On a Saturday morning final Could, Hubbard walked throughout a stage in New York Metropolis in cowboy boots to deal with a whole lot of attendees at Horizons, the world’s longest-running psychedelics convention. “I would additionally ask your conversational forbearance as I prepare to maneuver ahead, as a result of English is my second language,” he deadpanned, eliciting laughter from the viewers.

The jokes ended there. His eyes vast and burning, Hubbard spent the following 10 minutes delivering a CliffsNotes model of the earlier 12 months’s travails within the impassioned cadence of a Southern preacher. A number of occasions, the auditorium broke into cheers, forcing Hubbard to pause. Within the again row, Rick Doblin, the founding father of the Multidisciplinary Affiliation for Psychedelic Research, took a uncommon break from responding to emails on his cellphone and positioned a hand on his face as he thoughtfully listened. As Hubbard continued, Kevin Balktick, the convention’s founder, whispered to me: “Bryan is hands-down my favourite speaker—he is simply unbelievable.”

Hubbard concluded with a rallying cry that channeled his favourite verse from the E book of Isaiah: “I’m satisfied that if we of widespread thoughts, coronary heart, and soul, no matter political persuasion…make a dedication that we’re going to ship good tidings unto the meek, bind up the brokenhearted, proclaim liberty to the captives and the opening of the jail to them which can be certain—We! Shall! Win!”

The group burst right into a standing ovation.

Hubbard has turn into a hero within the psychedelics group. He has attended dinners held in his honor the place he was seemingly the one Republican within the room, and he has been a key visitor at unique conferences with rich figures funding the motion to legitimize mind-altering medicine.

Hubbard’s efforts to search out one other taker for the thwarted Kentucky trial have additionally picked up pace. He’s speaking to officers in Ohio, Washington state, Nevada, Missouri, New Mexico, and Arizona—plus a “darkish horse” state that he has sworn to not reveal—about leveraging their assets to foster ibogaine analysis. In July, a person linked to Georgia’s opioid settlement fund contacted him to inquire about ibogaine. “There’s a whole lot of curiosity that ranges from introductory exploration all the best way to deliberative consideration of ‘if’ and ‘how,'” Hubbard says.

Of the doubtless states, he says, Ohio, New Mexico, and the darkish horse are the furthest alongside, and he’s hopeful that a number of of those states will quickly “break the dam open.” He has met with Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine and “prime officers” within the thriller state. In New Mexico, he has had conferences with state Rep. Andrea Romero (D–Santa Fe), who has facilitated gatherings with officers from Picuris Pueblo, a Native American group in Taos County.

“They need ibogaine entry as rapidly as it may be negotiated,” Hubbard says of the Picuris Pueblo officers. If that occurs, information collected in Picuris Pueblo could possibly be compiled into a security and efficacy research that paves the best way for a proper FDA trial carried out by researchers on the College of New Mexico.

Mulligan is engaged on a plan for these states to kind a coalition to develop a generic ibogaine utilizing their pooled opioid settlement funds. Though the Kentucky effort failed, Mulligan says, “it wasn’t for nothing” given all these developments.

Hubbard is extra cynical right this moment than he was earlier than he heard the phrase ibogaine, however he’s additionally extra dedicated than ever to shepherding the drug throughout the FDA end line. “My first and solely goal that I’ve in life proper now,” he says, “is to attempt to do all the pieces that I can in no matter manner I can to advance [ibogaine’s] availability as rapidly as we are able to.”

*UPDATE: This text has been up to date to mirror information that occurred after the October 2024 concern went to print.

This text initially appeared in print underneath the headline “The Psychedelic Emancipator of Kentucky.”

[ad_2]